04 Feb ASIL Space Junk Panel Discussion

By Nathaniel Snyder

Why will orbital debris grow in number for the next 200 years even if no additional objects are launched into space? Does creating space junk violate international law?

The American Society for International Law (“ASIL”) recently hosted a panel discussion dedicated to all things space junk, including the questions raised above. The panelists, Jessica Noble and Steve Mirmina, are both prominent space law experts. Noble serves as General Counsel to NanoRacks LLC. Mirmina is a Senior Attorney at NASA, as well as a professor of space law at the Georgetown University Law Center. With the discussion firmly rooted in international space law, the panelists the examined the practical and legal implications of space debris existing outside traditional national jurisdictions.

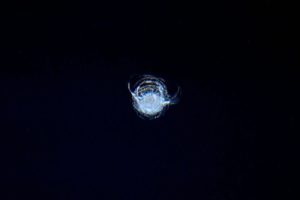

Damage on ISS window suspected to be caused by paint fleck

Space debris, or space junk, encompasses both natural (meteorites) and artificial objects. The overwhelming majority of orbital debris is man-made. Today there are more than 20,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball and tens of millions smaller than a centimeter. But traveling between 4 and 5 miles per second means even flecks of paint have potential for destruction. The number of objects will only grow as debris collides with one another producing smaller fragments that continue the cycle. This cascading sequence is known as the Kessler Effect. While most debris will burn up in the coming decades upon re-entry, the highest orbits will harbor junk for millennia.

Orbital debris also poses legal problems. Objects in orbit are outside traditional national jurisdictions. The Outer Space Treaty, widely regarded as the “Magna Carta” of space law, provides in Article VIII that ownership and control of an object does not end in space.[1] The provision expands this protection to component parts of space objects, so even paint chipped off a defunct satellite remains the registration state’s property. But the panelists considered a potential solution within the same treaty. Article IX mandates states observe “due regard” and conduct activities “so as to avoid their harmful contamination.”[2] Because space powers have long created debris when operating in space, this article doesn’t make debris creation illegal. It may, however, provide legal basis for organizations to begin cleaning space. An important distinction lays between cleaning the debris currently in orbit, known as active debris removal, and guidelines for responsible activity, known as space debris mitigation.

Astroscale was mentioned as a driving force behind commercial efforts. The Japanese firm’s ELSA-d satellite is scheduled for a 2020 in-orbit demonstration. NASA’s laser broom is another developing solution that heats the side of an object to change its trajectory. The broom could be used for collision avoidance, as well as active debris removal if the trajectory is diverted towards Earth. While it’s unclear what will stem the growth of orbital debris, international cooperation will undoubtedly be part of any solution. And it’s important that panels like this continue to advance the discussion.

To subscribe to the Journal of Space Law, click here.

—————

Nathaniel Snyder lives in Washington D.C. advising a U.S. congressional office as a space law fellow, as well as being a full-time student within the National Center for Air and Space Law. He’s currently a 2L student editor for the Journal of Space Law.

[1] See Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies art. VII, adopted Dec. 5, 1979, 18 U.S.T. 2410, 610 U.N.T.S. 205.

[2] See Outer Space Treaty, art. IX.